My Journey within the Embedded Domain part 3

2019

At the start of this year, our then-flagship microcontroller, the DA1469X range, wanted to get into the automotive segment. Concerning this, my usual HTOL (High-Temperature Operating Life) test activities have now been re-assigned to be able to construct the Early Life Failure Rate (ELFR) test program. This ELFR was consistent in its ideas concerning HTOL. Both these tests are meant to stress the various advertised features of the flagship microcontroller. During my time constructing the microcontroller firmware for the ELFR test, I was provided with the specification document which indicated the kind of stress that had to be applied to the various peripherals and features of the microcontroller. Also, it is worth noting that, unlike HTOL tests, the ELFR tests had no tolerance for failures. My task managers have specifically asked to ensure none of the 100s of devices in the industrial oven at temperatures higher than 100C should fail over the time of the test.

On the page “My Journey within the Embedded Domain part 1”, I briefly introduced the term DCTMon, this was a microcontroller evaluation suite constructed using legacy C++ and MFC frameworks with multithreading concepts. I’ll briefly note here what that tool does and what I had to do with it over the years.

DCTMon

New microcontrollers that Dialog produces have to go through several departments inside the company to be rigorously tested. Before tape-out, these microcontrollers exist as emulatable IP designs running on high-end FPGA fabrics. After tapeout, these devices would be actual silicon. During both these cases, if the user, had to talk to the fully functioning DUT, it would make sense for them to talk to the device through the SWD protocol (software debugging protocol from ARM for cortex-M devices). On the same topic, before the adoption of ARM cortex-M, Dialog had MIPS processors and XTENSA processors that communicated with similar JTAG/debug protocols.

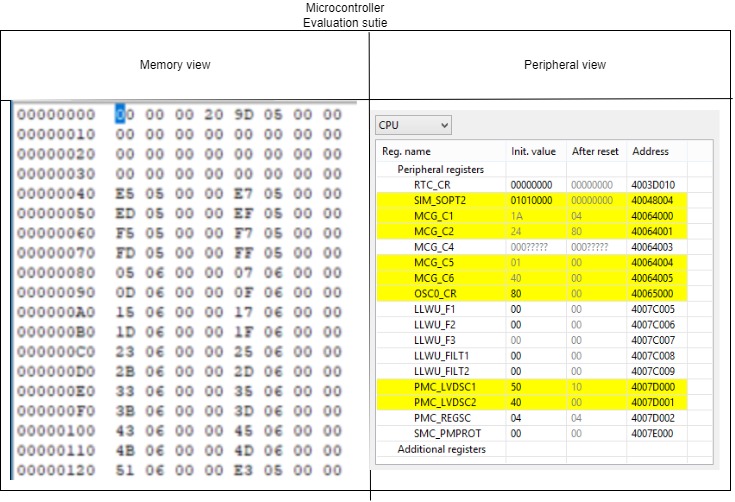

The DCTMon software enabled the engineers to talk with the microcontrollers to (1) view the memory contents of the entire addressable memory space (2) Write to the writeable regions of the memory space with 1/2/4 byte data or contiguous regions of data (3) Investigate the individual bits of various microcontroller peripherals in the peripheral memory space (4) Modify/write to individual bits of various microcontroller peripherals in the peripheral memory space (5) get a barebone scripting environment which can take a list of memory read/write commands in sequence to manipulate the microcontroller operation

This is a very basic visual indicator of such a program.

Naturally, the DCTMon was able to support 10s of different microcontrollers that Dialog produced. This was mainly tackled by the fact that the DCTMon suite had inbuilt definitions for the various microcontroller peripheral memory space. This meant that DCTMon knew about the various peripherals and bits of the various peripherals for all the microcontrollers that Dialog created.

One last fun fact about DCTMon was its learning opportunity for me to discover the ability of C programming language to handle dependency-inversion or run-time polymorphism. This was my first introduction to the world of programming design patterns. Some range of microcontrollers that Dialog produced ran/executed its application from an external QSPI/SPI flash. DCTMon was able to talk with and expect different SPI/QSPI flashes to be connected to various microcontrollers that booted from these flashes. DCTMon handled this by defining individual modules in the C program to handle different vendors of flash chips. All these individual modules used the same generic single SPI read/write routines but all these modules had their manufacturer recommendations of flash commands and wait times. During the start of the talk between DCTMon and such microcontrollers, DCTMon would send JEDEC commands to identify the flash and start initializing the concerned module during run-time.

Python-based DCTMon

The original DCTMon being old with multiple creeping bugs, was designated to be phased out in favor of the same tool being re-written in Python. Python won here as it was a source and an easy-to-use language. Any engineer in any team could take up such a Python-based DCTMon and customize it to their needs whereas that was not possible with the legacy DCTMon. I was tasked with this operation. Since I had a fairly good understanding of how the DCTMon was supposed to work, I leveraged the Jlink APIs to do basic memory read/writes and peripheral modification on the fly. A quick working demo was reached within a month of working on it.

My first introduction to the Software Development Kit (SDK) and FreeRTOS

Having heard this term, SDK, throughout the years, I never really bothered myself enough to understand what it exactly meant. Now, I was given a professional introduction to it. An esteemed colleague, Nikos Vokas, from the Greek software team wing of Dialog, visited us at our site at DenBosch for a week. During that week, he had planned for the embedded software team, an in-depth introduction to the SDK offered by Dialog for the range of microcontrollers that it advertises.

To put it simply, SDKs are a package of usable modular units of firmware/software that are designed to jumpstart/kick off the rapid development of applications on the intended microcontroller/target hardware. For instance, the SDK provides you with all the interface APIs a developer would need to initialize, read/write to a peripheral, and use a peripheral. The SDK would also hold many example programs that show the optimized ways of using peripherals/features on a microcontroller, right from the startup application to the run-time application.

We practiced the SDK training on our DA1469X dev kit and the latest SDK version of that time. Nikos introduced to us FreeRTOS and its APIs. The SDKs from Dialog have FreeRTOS built within them. The user can develop applications bare-metal or leverage the provided RTOS. The FreeRTOS training was super interesting as it was my first professional experience with an RTOS. Various cool features of FreeRTOS such as Queues, Task notifications, Task creation, Task deletions, Semaphores, and Mutexes were taught and demonstrated.

My experimentation on the same can be found here:

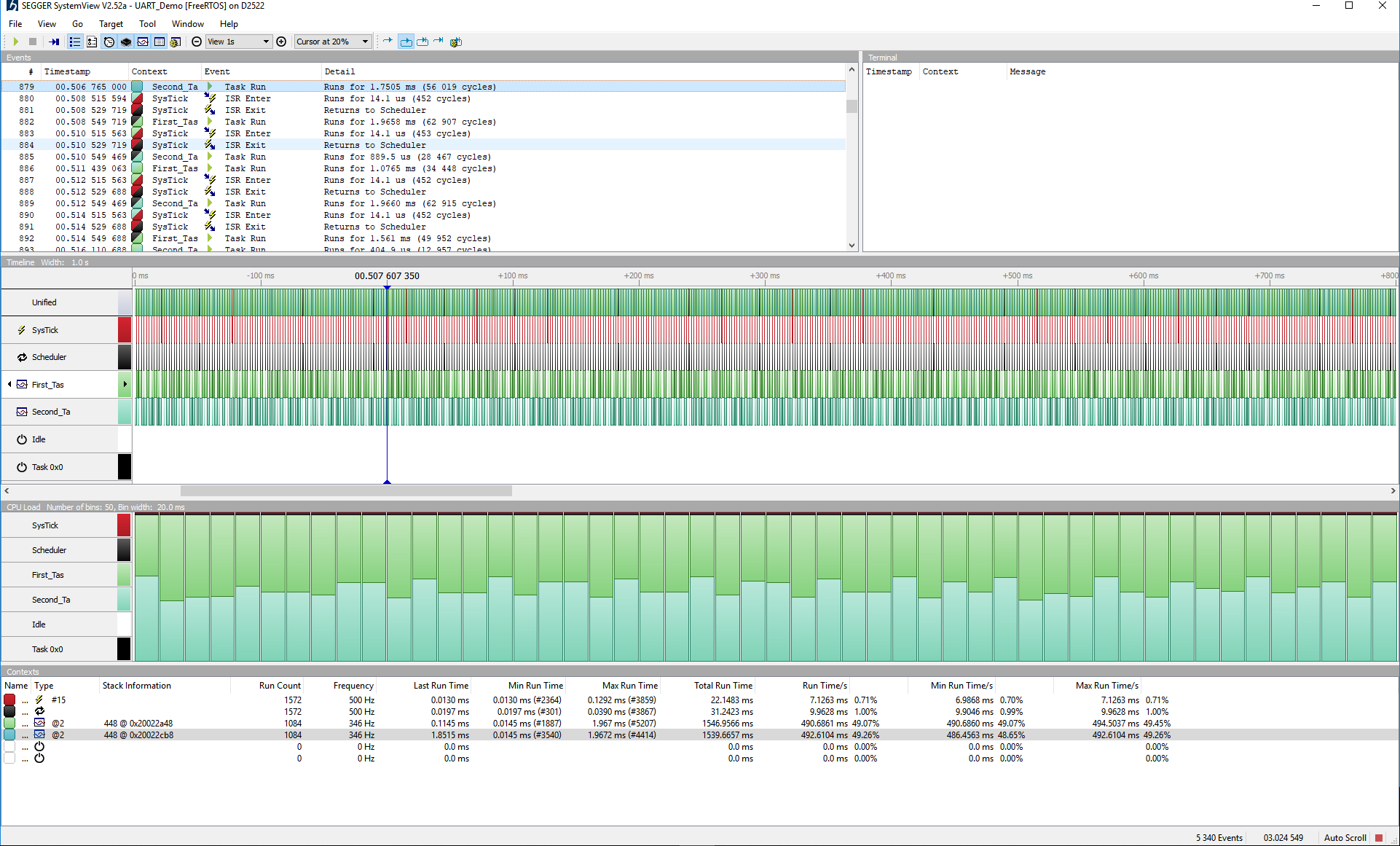

The demonstration of FreeRTOS indeed piqued my interest. I took on a fairly informative introductory course on FreeRTOS demonstrated using STM Nucleo boards. This course by Kiran from FastBit labs, as usual like his other courses, was excellent. In addition to seeing the features of FreeRTOS being explained and demonstrated, the course introduced a nice debugging tool called systemview from Segger. This tool was extraordinary as it gave clear pictorial representations of the system and its level of utilization with the tasks being visualized as bar graphs.

By the end of the year, I accidentally found an amazing book from Robin Heydon called as Bluetooth Low Energy: The Developer’s Handbook. This book had everything I needed to know about the BLE stack-level details.

Also, I was able to brush up my knowledge on ARM cortex-M architecture from a Udemy course from Kiran, called Embedded Systems Programming on ARM Cortex-M3/M4 Processor. This was a good refresher course on cortex-M for me. It reminded me about the Doulos training where all these were already taught for me.